The Use of Bodies by Diana Padrón “No soy un objeto sexual” [I am not a sexual object] could be a political slogan against the objectification of the body, or perhaps a social program on feminist empowerment in the face of porn culture. Indeed, the pornographic image fragments and objectifies genitality, and this fragmented image also speaks to us of an existence torn apart by the devices of indexing and accumulation of Big Data, where lustful images of sexual exchanges abound. In the age of the ubiquity of pornography, smart sex toys, and the normalization of dating apps, one cannot a priori state that sexuality is a transgression. In fact, late capitalism appears to be endorsing it all. Not coincidentally, in his theory on fetishism, Freud took a concept previously developed by Marx from a critique of capitalism, which points not only to the reification of the body but also to the commodification of desire. That is why “No soy un objeto sexual” could even stand for the rebellion of an army of dildos that have organized themselves to claim another role in society, like the one given to them by Paul B. Preciado in Manifiesto Contra-Sexual (Preciado, 2000), where the deconstruction of sexual practices and genitality leads him to announce the primacy of the dildo over the penis, adopting the theory developed by Jean Baudrillard (Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 1981) that the image precedes reality. However, the project “I am not a sexual object” goes beyond a posthumanist assertion. Neither the installation L’intrus (2022) – composed of the stock of a sex shop and a piece by ceramist Cécile Ribas – nor Das Über-Ich [Superego] (2022) point to autoerotic technology, but rather to the semantic technology of images, objects, and language in determining their sexual nature. Such a cosmology of meanings makes the overdose of sexual signs that flood our daily lives explicit while denying their incompatibility with their radical antagonism: repression. As Sade and Pasolini have demonstrated, every conservative morality feeds a counter-morality given to depravity. It is no secret that these days, the massive consumption of PornHub images is matched by millions of censored images every minute on social networks. Likewise, as an act of libidinal catharsis before the imminent promise of fidelity, bachelorette party ceremonies represent a grotesque and trivialized version of conservative culture. The artist Nathalie Rey (Saint Germain en Laye, 1976) plays ironically with these contradictions in works such as The Censor, the Censor’s Son and the Artist (2022), a mural and an installation of erotic magazines in which she addresses the obsession of one generation to censor pornography, only to awaken the traumatic desire for such images in the next. Referring to the film The Cook, the Thief, his Wife and her Lover by Peter Greenaway (1989), the artist adds to the chain of censorship by tearing out the philosophical pages of the novel Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue (Sade, 1791), of which only the explicitly sexual ones remain, indicating, perhaps, some other form of taboo lurking in the background. Moreover, it is impossible to ignore the acid sense of humor that floods the entire “I am not a sexual object” project, as it investigates the intricate, dark, and disturbing articulations of desire, for instance, in the series of photographs El Destape (2022), or the soft sculptures Rabbits (2022). This unconscious desire refers to the infantile character of eroticism, which, according to Georges Bataille, manifests itself fundamentally through play (Bataille, Eroticism, 1957). In this sense, it is no accident that Nathalie Rey’s project contains numerous mythological evocations of an original nest – a lost paradise – in the primordial stage of humanity, in which life might have been filled with play instead of work and where the garden may represent the fullness of the erotic utopia: as in the stories of Gilgamesh, to the Mahabarata or the Eden of Genesis. The artist appeals to this ancient eroticism when interpreting The Garden of Earthly Delights (2022) by Hieronymus Bosch. Far from the repressive and moralizing sense that may have motivated the Renaissance painter, Rey recreates an exuberant orgiastic garden through a web of wool threads that extend through space, intertwining female breasts and male genitalia. Woven with the crochet technique, these genitals sprout and multiply like climbing plants on two chairs, no longer representing the phallus as a symbol of power but as an object predisposed to play. Of course, this garden is not lacking in a trail of fluids that, as in any erotic scene, lubricates everything that grows. All these questions about sexual objectification, repression, unconscious desire, and even the very nature of the erotic are formulated in “No soy un objeto sexual”. Based on the formal research of everyday objects that Rey carries out, with a particular interest in items intended for children, these concerns eventually materialize in artistic formats such as installation, video, photography, and performance. In the series of photographs El Baño (2022) or in the exhibition as a whole, as well as in previous works –Estado de Sitio (2021), Caca de Artista (2020-2021), Naufragio (2012-2021)- the accumulation of elements refers to the excesses of consumer society while questioning the uncomfortable contradictions of our culture. She uses dream-like rhetoric that may remind us of the work of Louise Bourgeois or contemporary artists such as Laure Prouvost, but radically distanced from the tendency toward dogmatic surrealism or certain essentialist conceptions of the feminine. Instead, she is interested in investigating the paradoxes and concerns that permeate humanity from a subjective perspective that is ironic and tragic at the same time, reminiscent of a dialectic typical of psychoanalysis. According to Freud, culture may have had its ancestral origin in dreams, in which humanity’s stark reality becomes present as a disturbing juxtaposition of two different realities (Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, 1899). This is how the duality “life drive” -or Eros drive- and “death drive” -or Thanatos drive- arises, found in equal parts in eroticism, inviting us to think about the possibility of objectification, of self-objectification as a form of desire in the game of eroticism. The philosopher Giorgio Agamben reflected on the “use value of bodies” as opposed to their capitalist exchange value (Agamben, The Use of Bodies, 2015). While the latter alienates subjects by turning them into mere interchangeable merchandise, use-value makes the body an “object of desire” that can satisfy a need only to the extent that it is considered from its particularity and from such a degree of importance within a permanent game of relations of uses between some bodies and others. In other words, such self-objectification could be understood as a form of empathy that allows us to take the place of the other, something that can also happen, for example, in the performance of an artist. As Bataille well knew, what is at stake in eroticism is the dissolution of previously constituted forms. This desire for dissolution, for life and death, for being subject and object simultaneously, could not be better represented than through the erotic metaphor of the petite mort.

no soy un objeto sexual

Embroidered fabric

92 x 100 cm

2022

Embroidered fabric 92 x 100 cm 2022

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Installation with garden chairs, crocheted penises, silicone breasts, wool, hose and nest

105 x 300 x 200 cm in its provisional version

In progress

The space of the garden is suggested by an interlacing of thick woolen threads that "creep" on the ground, "climb" on the furniture, and in which twenty silicone breasts are placed. Likewise, the chairs are invaded by curious plants in the form of crocheted penises sewn into the seats.

It is a wild, exuberant, and luxurious garden–a paradise of Adam and Eve, only after the sin. Hence the reference, through the title, to the work of Hieronymus Bosch, which represents countless scenes of pleasure involving fragments of bodies. Due to the religious framework of the artistic production of that time, it is clear that the viewer was faced with the very Catholic vice of fornication. This is also the question that implicitly arises in the homonymous film by Carlos Saura (1970) in which sexuality, repressed by a conservative society embodied by the Cano family, can only be expressed unconsciously.

The installation is a dreamlike scene, somewhat grotesque and monstrous, which could have been taken from one work or the other, a sort of symbolic painting, an expression of an unconscious desire, but where the notion of vice is replaced by that of fantasy and play.

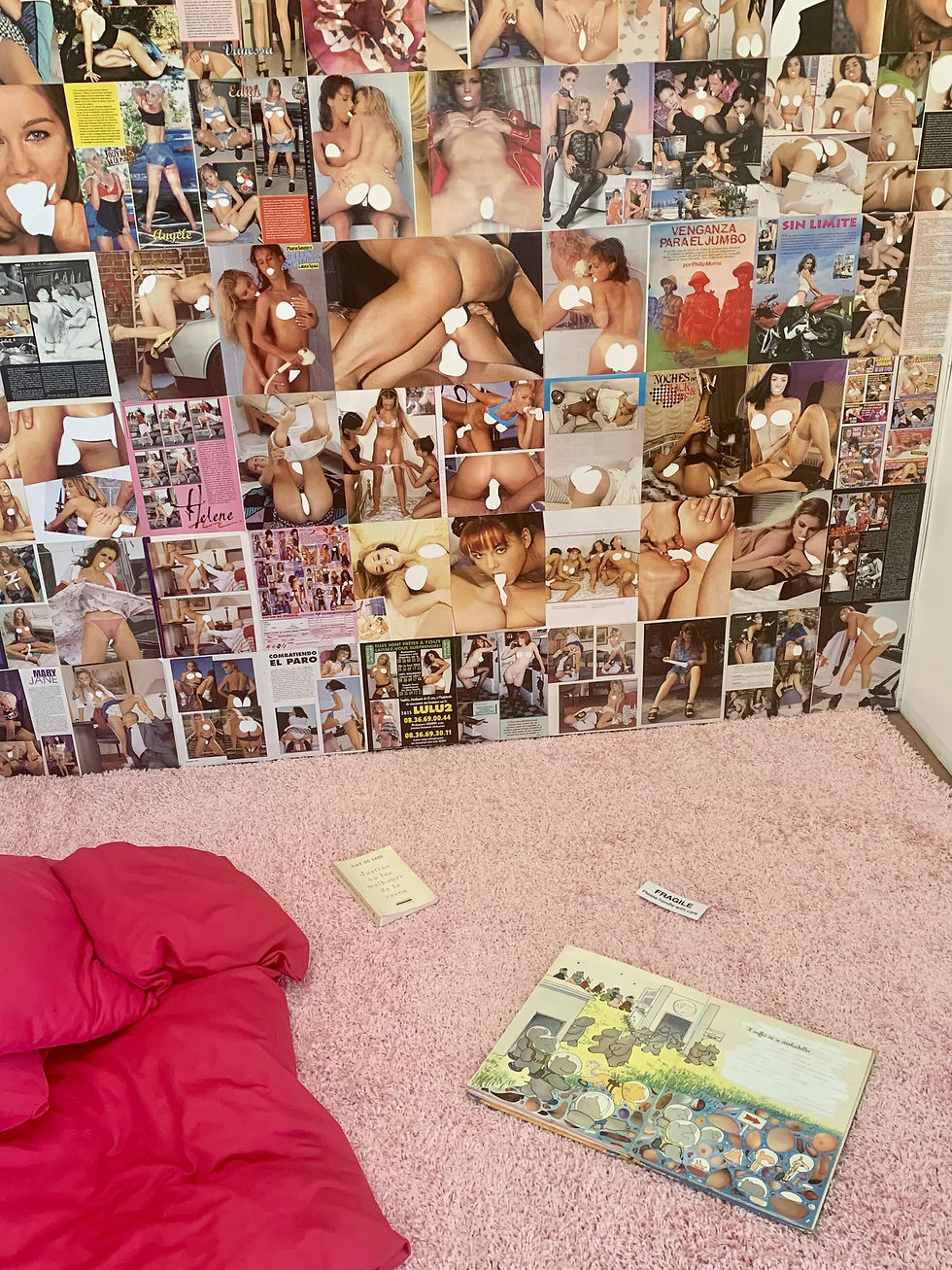

The Censor, the censor’s son and the artist

Installation with mural made of scalpel-cut pages taken from porn magazines, stack of porn magazines, a novel by Sade and an album by Babar both modified

Provisional version

In progress

All eras have had their organs of censorship; In Spain, conspicuous examples include the Inquisition or the dictatorship of Franco (referred to in another part of the project). Today, despite the evolution of much of the world towards democracy and freedom of expression, censorship still exists everywhere and at all levels of society.

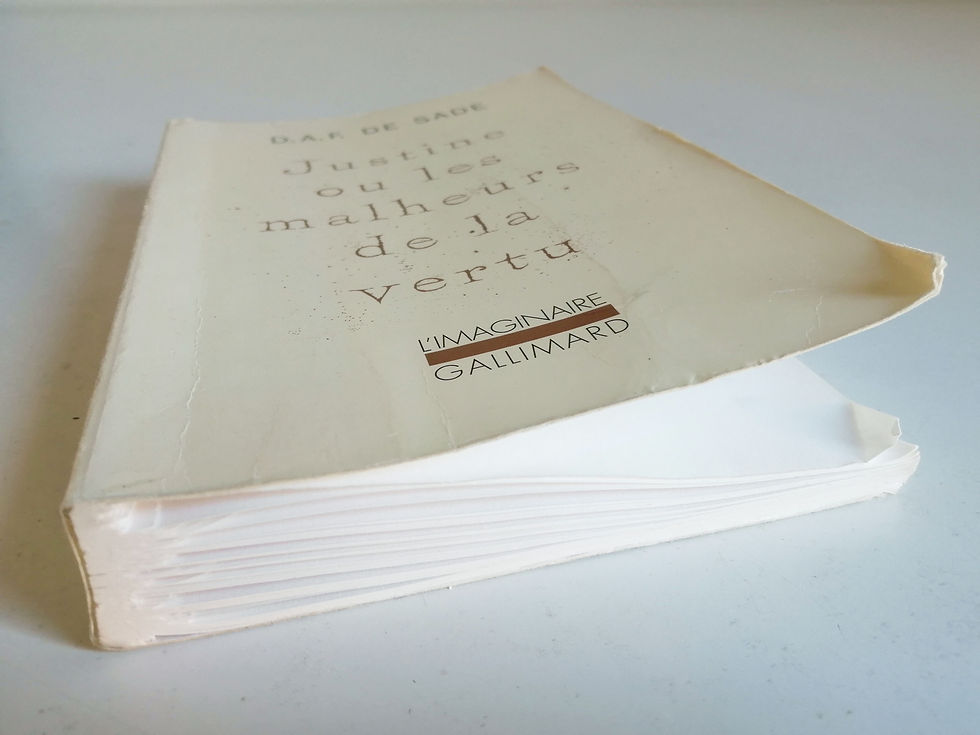

This installation, in progress, is the story of a meticulous censor who has given himself the task of eliminating all the vaginas, breasts, buttocks, lips, penises from all the pornographic magazines that fall into his hands. His son, intrigued by these cutting sessions, collects lost papers and pastes them into his Babar album. And since it is a fable about the cycles of censorship, the artist intervenes in her turn with her barbaric cutting of the novel by the Marquis de Sade, Justine or the Misfortunes of Virtue (1791), from which she removes the pages that correspond to the philosophical reflections – after all, boring – saving the sex scenes in an inverted act of censorship.

L'Intrus [The Intruder]

Set consisting of Plexiglas shelves, sex toys and a ceramic sculpture by Cécile Ribas

Provisional presentation

In progress

Detail

Babar's album modified

Novel by Sade with pages torn out

The Bath

Set with a selection of photos from the homonymous series and soaps made from molds of vaginas by Lejlac

Variable dimensions

2022

Photographic series

Photographic series

Photographic series

Photographic series

Photographic series

Photographic series

El Destape

Photographic series in progress

Digital prints on HP Universal Instant-dry Satin Photo paper

40 x 30 cm each

Ich bin nicht Klein

Performance